It’s less than 48 hours to the opening ceremony of the XXXI Olympiad – the 2016 summer Olympics Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. One athlete that will be conspicuously missing in Liberian colours is the African nation’s flag bearer at the 2012 Olympic Games in London, Phobay Kutu-Akoi.

The 28-year-old sprinter not only missed her chance to qualify for the Rio 2016 Olympics in June this year, but laid helpless – neglected by her federation officials – in an immigration detention centre at the Johannesburg Airport when her colleagues were warming up for their events at the African Championships in Durban.

Here, Phobay narrated to us exclusively on AthleticsAfrica.com her ordeal in the hands of the Liberian Athletics Federation and her 48-hours of hell in her quest to serve her fatherland…

“Your federation failed you.” These four words, spoken by a perfect stranger, summed up not just the last 48 hours, but also the last seven years of my relationship with the love of my life, my country.

For seven years I had literally put blood, sweat, tears, and money into chasing my dream of making my country proud on the biggest athletic stage.

All of that hard work culminated with me, alone in a jail cell, in a foreign country—most people’s worst nightmare. After all of the trials and tribulations, I had always stayed faithful to my craft and to my country.

Less than four years earlier, I had proudly carried my country’s flag at the London Olympic Games. So, what could I have done to get me here?

Confirmation

On June 17, 2016, I received a call, confirming that I and my Liberian teammates would be representing Liberia at the African Championships in South Africa, scheduled to start not even a week later.

I was instructed to book my own flight because, as usual, the federation, along with the Liberian National Olympic Committee, and the Liberian government were unable to fund their athletes.

The federation made sure to at least take the time to say that they were sorry for the inconvenience.

Inconvenience—a word that flows so easily off of the speaker’s tongue, but to the person who is “inconvenienced” can represent years of let down and heartache.

For me, “inconvenience” was perhaps the most dismissive way to sum up the seven years of me working a full-time job to pay for training and recovery, while I waited for the federation to deliver funding on time.

I worked from 1:30 PM to 10 PM during the summers and 3 PM to midnight during the winters, just to allow for me to maximize the amount of training that I could do during daylight hours.

“Inconvenience” included me having to take 5 weeks of unpaid leave from work, to allow my body time to recover from the grueling practices in preparation for the Rio 2016 Olympics.

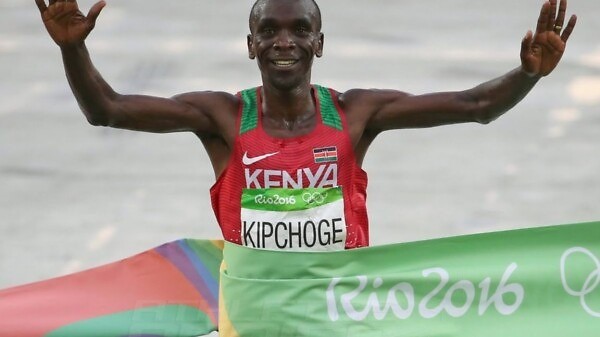

Phobay Kutu-Akoi carrying the Liberian flag at the Opening Ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics / Photo Credit: Phobay Kutu-Akoi

Visa problem

On Saturday, June 18, 2016, four days before the start of the African Championships in Durban, I received a call from a federation representative stating that there may be a problem with my trip to South Africa.

Since I was the only Liberian athlete still holding just a Liberian passport, I was the only one that also needed a visa to gain entry into South Africa.

Earlier that same day, I had finally received an emailed invitation letter for the event, so I asked if that letter would be enough. We decided to try.

As I reflect on everything, I can only shake my head at how normal this lack of planning, communication, and support by my federation had become to me. I had emailed a scanned copy of my passport to the federation many times and no one mentioned that I needed a visa.

I flew into New York from Dallas and spent the night before going to the airport for my flight to South Africa the next morning. I showed the letter, explained the purpose of my trip, and was issued a ticket.

I was surprised at how smooth the process was but did not question it because I was focused on the purpose of the trip. I boarded the plane at 11:15 AM for my 14 hour trip to Johannesburg, feeling relieved.

I spent the first half of the flight reflecting on how good I was feeling. My time off from work was paying off because i was well rested and ready to race.

My flight landed at 8:05 AM on Monday morning, 2 days before the start of the event. When I arrived at customs, I was asked about my visa. I explained my situation about the invitation and the African Championships, and was subsequently ushered to a waiting room while immigration investigated my situation.

After immigration was finished with their investigation, I was told that I could not enter the country and that I needed to contact the Liberian consulate.

While waiting for the consulate to call me back, I was instructed to make a signed statement, acknowledging that I was an illegal foreigner and was denied entry into the country.

I was told that the next step was for me to board a plane back to New York, but in the meantime, I would be escorted by security to another area.

Two other foreigners and I followed the officer down a long hallway, took an elevator, and walked some more. We eventually got to a door that required badge access.

When the officer badged in and opened the door, I saw two jail cells and thought to myself, “wow this doesn’t even look like the airport anymore, so this must be where they keep the unmanageable people.”

At this point I did not know that this would be where I would spend the next 10 hours.

I explained my situation to the officer. As I talked, I could see the pity come on the officer’s face. He offered me food and water. I accepted the water, but declined the food, because I had no appetite.

I also still had faith that the Liberian consulate would come to my rescue and that I would be out in time for my flight to Durban at 1:55 PM.

Thrown in the cell

After being searched, the sympathetic officer put me in my own jail cell, away from the general population.

He also allowed me to keep my phone in case the consulate called. Before leaving, the officer explained that my only chance of gaining entry into South Africa was if the Liberian consulate hurried to the airport and talked to immigration.

“That’s what the Americans do for their citizens,” he said. The nice gentleman left the door to my cell ajar, perhaps to make me feel less like a prisoner.

There were two larger cells, one for the men and one for the women. There were metal doors between the bars and the cells, so I could not tell if there was anybody in them, until they let them out for lunch.

My cell was in the back. It was very cold—not sure if it was just the temperature or the overwhelming feeling of being abandoned. It had a bathroom that did not lock, no mirrors, and a shower with no curtain.

I brushed my teeth and sat down on one of the single beds and called my sister. On the inside, I was feeling scared and disappointed, but I remained calm and told my sister not to panic and to not tell my mother.

I assured her that everything would be cleared up soon. When I hung up the phone, I was back in my reality. I could not believe that this was happening to me.

To keep my sanity, I disassociated myself from the situation completely and began to read a book that I had packed. I tried to keep my mind off of the fact that I was alone, sitting in a jail cell in a foreign country.

By this time, I was freezing. Luckily I had my backpack with me, so I put my track tights under my jeans and put on socks. I started to fall asleep, when a female officer walked by. I asked her for a blanket and when she brought it, she said, “I think I should close the door since you are sleeping.”

I declined, attempting to hold on to the last piece of freedom that I felt I had. The officer insisted that she close the door as if I really did not have a choice in the matter, so I reluctantly agreed.

I fell asleep again. Around 3:30 PM, I woke up to find a man staring at me through the small diamond-shaped window of the metal door of my cell. He just stood there looking at me and then he waved, so I waved back.

At first glance, I thought it was another security guard. Then I realized that the man was actually a prisoner. I wondered how long this man had been watching me sleep.

What a violation of privacy? To know that a stranger was unknowingly watching me in my most vulnerable moments removed any last sense of security that I was holding on to. It now made sense that the female guard insisted she close the jail cell door.

I checked my phone for missed calls or messages. I had none. This is when I first began to cry. My flight to Durban had left and I was still alone in a country that I had never been to. I forced myself to go back to sleep.

Hope at last?

At 4:57 PM, a guard came to get me. “A representative from the Liberian consulate is here,” he said.

“Finally. Thank God this is all over,” I thought to myself. I immediately started thinking ahead. “Maybe I can catch the next flight to Durban,” as I planned out my next steps.

I sat down with the representative and he expressed sympathy. “This is a tough situation,” he explained. “If we don’t hear from the ambassador, you will have to go back to the States.” He asked me when I last ate. I told him that my last meal was breakfast on the plane, around 7 AM.

The head of security allowed us to walk to get food in the airport as long as one of the female workers was with us. I had no appetite at this point—I just wanted the whole ordeal to be over—but, I forced myself to eat a sandwich.

I kept staring at the representative’s phone, hoping it would ring with some news from the ambassador. It finally rang.

“Your excellency,” he addressed the person on the other side. He handed me the phone. “Do you have a green card,” the lady asked. I told her yes and she said she would call back with more information.

It was now 6 PM and the lady dining with us stated that it was past her shift so we had to go back. We got back and the representative from the consulate told me that he had to head back to Pretoria and suggested that I get on the next flight back to New York.

At this time, the night shift crew had arrived, and they did not seem as nice as the first shift workers. I was taken back to my cell and the door closed behind me.

I started to cry again. I am not sure if I was crying because my only chance of getting to the African Championships just headed home or if it was because the reality of the situation was finally hitting me—I had been in that cell for over eight hours and was still there with no idea when I was getting out—or perhaps it was both.

I wondered what crime I had committed that even the Liberian consulate could not get me out of. All I wanted to do was run for my country and have my chance of qualifying for the Olympics.

I thought back to one of the questions that the representative from the consulate asked me. “Why don’t you have a US Passport?” It was a good question. I explained that I did not apply for American citizenship because Liberia does not allow for dual-citizenship and I wanted to run for Liberia as a Liberian citizen.

Out of loyalty to my country, I wanted to run my whole career knowing that I only held a Liberian passport. It made me feel a sense of patriotism. All of the patriotism in the world could do little for my situation, though.

At this point, all I felt was betrayal. Since graduating from college, I had made all of my decisions based on what put me in the best position to represent Liberia. I did not run for the money. I put more money into track then it gave back to me.

I thought back to all of the competitions that I had to pay for myself because there were not enough funds for the athletes. Yet, we watched as Liberian officials arrived and went on shopping sprees, as if on vacation, with what was probably our per diem.

My teammates and I would always sit around and share our own stories of letdown by the federation at one point or another. We would all laugh. I think we laughed to keep from crying.

Being professional athletes for an underfunded country was hard enough without having our federation do everything to make it more difficult. As I sat in the jail cell, I could no longer laugh. All I had left was tears.

In spite of this, I thought about how much worse the situation could have been. What if the nice male guard had not placed me in my own jail cell? What would have happened if that female guard had not insisted on closing my cell door while I slept?

I began to think back to all of the other times that my federation had let me down.

I thought back to March of 2016, when I purchased my own tickets to the World Indoor Championships because the federation did not have the funds. The IAAF reimbursed me by sending the money to Liberia. I have yet to receive that money.

How about the time in 2015, when my teammates and I trained all year in preparation for the African Games in Congo, just to find out 10 days before the competition that we were not participating because the federation ran out of money.

Or the time in 2012 where I qualified for the 100m finals at the African Championships, only to miss the event because the delegate gave me the wrong schedule.

There was also the 2012 Olympics, where the federation, again, did not purchase our tickets. We were not asked for our clothing sizes for the opening ceremony outfits, so they included a one-size fits all gown, even though our athletes ranged in height from 5’3” to 6’3”.

I was provided a Men’s size 9 Sketchers brand sneaker with basketball shorts and a basketball jersey that said Liberia on the back, none of which could I use or let alone fit in. We ended up having to go shopping for our own opening ceremony outfits.

I thought back to all the excuses I had been given over the years—even the times when I was told it was my fault for not double checking what my federation had told me.

All of those moments of disappointed brought me to this point. Eventually, I boarded an 8:55 PM flight back to New York.

Deportation

Liberia’s Phobay Kutu-Akoi during the women’s 100m semi-final at the 2010 African Senior Athletics Championships in Nairobi, Kenya / Photo Credit: Yomi Omogbeja

When I arrived in New York on Tuesday morning, I made a last ditch effort to get a visa so that I could fly back to South Africa because I did not want to end my track career this way.

“Where is your visa application? This was supposed to be completed online. You also need two passport sized photos and a money order of $36. And, you’re telling me that you want to fly out today? No ma’am. It may take up to two weeks for this to get approved. Here is the form.”

This is what I am being told by the receptionist at the South African consulate in New York, a day before the African Championships are set to start.

I took the form from the receptionist, thanked her, and went into the waiting area to fill it out. I only had one passport sized photo in my wallet with cash and credit cards, but no money order.

One question on the form was “Have you ever been restricted or refused entry into South Africa?” I hesitated and checked yes.

I went back into the office with the completed form and begged the lady to speak with the consular, hoping that having heard my story, he would expedite the process and grant me a visa so that I could get on the 5:40 PM flight from D.C to South Africa, my second 14.5 hour trip to the country in the last 48 hours.

A gentleman approached the window, already shaking his head. I handed him my passport, itinerary, and two letters: one was the invitation and the other was a letter from Technical Manager of Athletics stating the requirements for gaining access to South Africa.

After glancing over the letter, the consular asked, “Well, what do you want me to do?” “Sir,” I pleaded, “I would like for you to please approve my visa application so that I can get on the next flight to South Africa to compete at the African Championships…”

“This competition starts tomorrow. There’s no way you’re going to make it in time,” he quickly responded.

He gave me a stern look and said, “This letter was sent to you on May 26, why are you just now coming to the consulate today?”

I explained, “I received this letter from my federation on June 18th, the same day as my flight from Dallas to New York, and…,” as his paper shuffling interrupted me.

“You’ve missed the date to fly out anyway. This itinerary says June 19th, today is June 21st,” he said. I explained that I had in fact flown to South Africa and had been sent back due to not having a visa.

“You flew to South Africa? How, without a visa?” He questioned. “I presented the same letter to ticketing along with my passport and was issued a ticket.”

“Did you not read this letter? You should have never been booked on that flight, but it’s your fault. I can maybe get you a visa for Thursday but that is not enough time. You are an athlete. You needed to be there five days ago to rest,” he scolded me.

“You know how many people I turned away last week? Five! Because they all came in when it was too late.

“We’ve known about this event for a while now. You federation knew about this event. Your federation failed you. There is no way I can grant you a visa for today.”

Dejection

Dejected, I walked to the elevator to make my way back to JFK Airport. I looked down at my swollen feet barely still able to fit into my sandals.

Three hours from Dallas to New York. 14 hours to Johannesburg. 10 hours in a jail cell. 14 hours from Johannesburg back to New York. I was still wearing the same jeans and t-shirt from Sunday.

The gentleman’s words played back in my head over and over again. “Your federation failed you.” He was right. My federation failed me and had been failing me and my teammates for the majority of my professional career.

Carrying only my backpack and purse, I walked back to the airport. My luggage was missing—it probably continued on to Durban, where I was supposed to be by now—plus I had no return flight to Dallas, since I planned to come back on June 27, after the championships.

I felt defeated. Missing out on the African games, meant I missed out on three opportunities to qualify for the Olympics and I am out of track meets. The deadline is July 11, so this is basically it.

Out of my unwavering loyalty to my country, I decided to keep quiet, at first. I changed my mind when I thought about the careers that this foundation has ruined and will continue to ruin if something does not change.

I am writing this for the Liberian athlete that will be top 10 in the world, only to be let down when the federation forgets to submit their name to the IAAF.

This is for the Liberian athlete that will have to spend their own money to fly to another country for World Championships, while federation officials order room service while staying in the best hotels, all paid for with the athlete’s refund.

This is also for the athletes that qualified for championships, packed a bag, only to find out at the airport that the tickets promised were a broken promise.

I do not want any more Liberian athletes to show up ill-prepared for events, all wearing different uniforms from different years, because, again, the federation does not have the funds.

For the person reading this and thinking, that I should just not be telling my story because, “Hey T.I.A. (this is Africa),” I say “you are part of the problem.”

Liberian athletes have just as much talent and work just as hard as athletes from other countries. T.I.A. is no longer a valid excuse for officials to misuse funds from the federation to fund their vacations, while the reason for them having jobs—the athletes—struggle to make ends meet.

When these officials are given these important titles, the purpose should not be for them to travel abroad. Their focus needs to be on giving their athletes the opportunities to be successful.

We are from a country that is only on the news when it has to do with civil unrest, corruption, or most recently, Ebola. Why would we not do everything we can to make sure positive figures like Liberian athletes shine?

The purpose of this is not to bash Liberia or the federation, but it is to finally tell my story. Writing this has been therapeutic for me in so many ways and I can only hope that it brings about awareness and forces a change.

We as Liberian athletes have so many odds stacked against us and it is about time our Federation stopped being one of them.

(Love this? Share this story: [wpbitly])

Editor’s note:

What do you think we can do to stop these endless let down of athletes, corruption and bad governance in African athletics, and sport federations? Do join the conversation on Twitter, Facebook and Viber

.png)